Why Friction is Still a Watchmaker’s Greatest Enemy

Dr. Samuel Rowley-Neale, an advanced materials scientist at Manchester Metropolitan University, in the UK, and an enthusiast for tribology (the science and engineering of understanding friction) admits that he was surprised when he started looking into the world of horology. “Really there’s been very little in the innovation in terms of how lubrication is used in watch movements for hundreds of years,” he says.

What efforts there have been, he adds, speaking frankly, do not really stand up to analysis: “Very often the application of advanced materials [to improve lubrication] turns out to be more about decoration. They’re gimmicks, with very little work having been done on the hard science of actually lowering friction.”

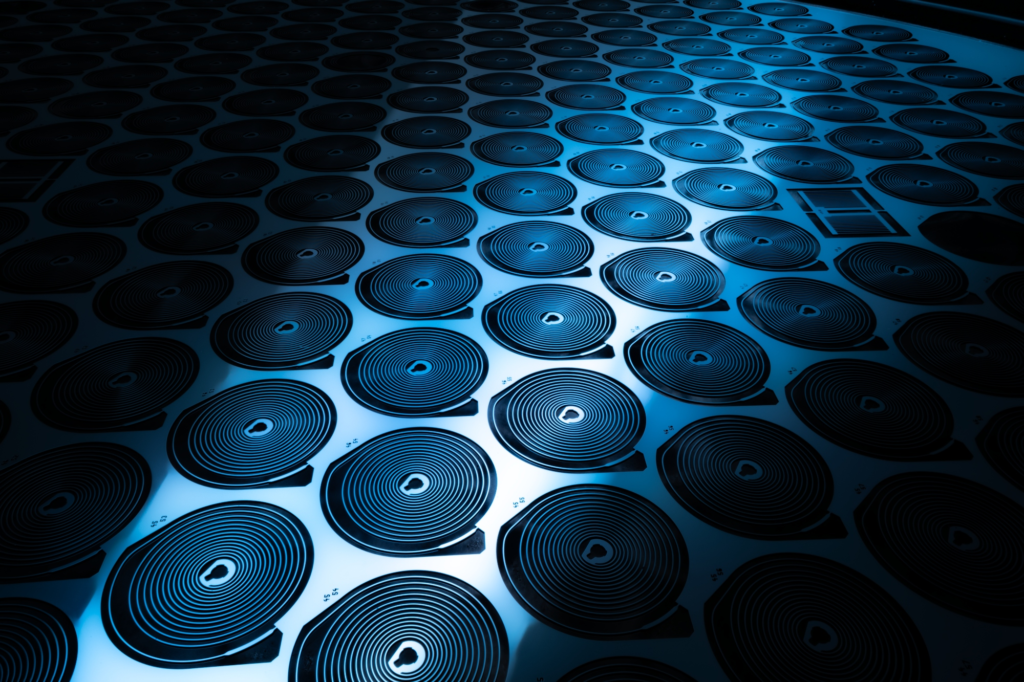

He is not surprised by that at least: there are plenty of highly specialist boffins who have worked on “blue sky research” for years using incredibly advanced pieces of equipment – costing millions – only to make limited advances themselves. Indeed, maybe he and his colleagues are on the brink of a breakthrough: for the last couple of years they have worked with the British watchmaker (and living legend) Roger W. Smith to develop a 2D molybdenum disulfide-based nano material, similar to graphene – for patent reasons they are tight-lipped about details. This might be used to coat certain watch movement parts to bring about a measurable reduction in friction.

PROOF OF CONCEPT

This coating is, as he puts it, “well known to be lubricious. The trouble has been finding ways to allow it to be sticky and stable and lasting.” Critically then, they have also developed proprietary methods of hybridisation (embedding the material in other carbon-based materials to fix it) and of deposition – how to get this material onto small parts in a way that is consistently even. That is something that the application of ultra-thin, extremely hard diamond-like coatings (DLCs), among recent friction-reducing technologies, has yet to pull off satisfactorily. Rowley-Neale and co now have a proof of concept with one of Smith’s watches and are shortly set to establish a multi-university team (with specialists at the University of Birmingham) to refine this further.

“Of course, understanding this material, being able to consistently replicate it and being able to say it will do this [reduce friction] and do that consistently too is very hard,” Rowley-Neale concedes. “If we can crack its use in watches – at such a small scale – then we can see it following the F1 model and trickling down to other industries the likes of aerospace and automotive.” His best estimate? Three years until they have an industrial-scale methodology.

That is a telling phrase. Over the last 20 or so years, several brands have introduced pioneering technologies that aim to reduce the friction between the many parts of their movements but invariably these have been showcased in one-off (or extremely limited-edition) experimental watches, as their names often suggest.

There has been Ulysse Nardin’s Freak, the first watch to etch its two escapement wheels from slippy silicon rather than the usual steel, with the brand having since experimented with parts made from cultured diamond. Patek Philippe has tried a similar concept but in the form of the standard Swiss lever escapement, while Audemars Piguet’s Cabinet No.5 offered a calibre with oil-free pallet stones. Cartier proposed its ID One and Jaeger-LeCoultre made the Master Compressor Extreme LAB – with its oil-free silicon escapement, a self-winding mechanism using ceramic ball-bearings and patented use of black diamond and something called Easium Carbonitride.

WATCHMAKING GRAIL

But for anyone wondering why there is this all this effort being made at all, it comes down to two words: physics and oil. In short, in any mechanical action, friction between the parts reduces their efficiency – that is, increases the energy required – and, with a machine that is all about precision, efficiency is key. To minimise this friction, and so also to reduce wear and tear on the parts that comes through all that rubbing, the watch industry has, since day one, used oil. As Abraham-Louis Breguet may or may not have actually said: “Give me the perfect oil and I will give you the perfect watch.”

You can see feel his frustration though. Oils were originally organic – often extracted from boiling the fat glands in the feet of cattle, since you asked. They were highly volatile and over time would oxidise, coagulate – especially when mixed with the microscopic dust from all that that wear and tear – or evaporate. Around 50 years ago, a menu of dedicated synthetic oils – still used today, in amounts so tiny as to be virtually invisible to the naked eye, with around 1/1000th of a millilitre enough for an entire movement – were a world better. These extended the advised time between servicing from two years to five or more. The oils keep getting better – and have some fantastic, MCU-like names, from Moebius to Molykote – but they still degrade eventually.

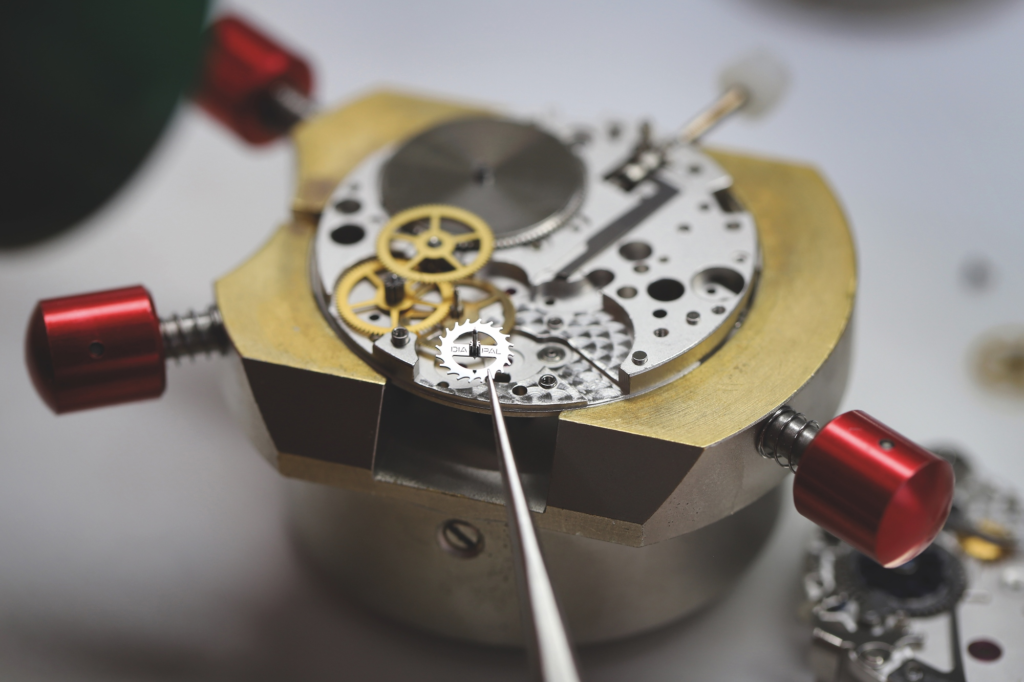

That, in large part, is why a mechanical movement needs periodic servicing – to clean it, but also to replace the oil that was applied to the 60 or many more points when it was first assembled. Different points need different types and quantities of oil, prevented from spreading by what is called an epilame surface treatment. Today most lubrication is handled by robots with inkjet printer-like shooters.

FATIGUE HAPPENS

Baumgartner agrees: he says that experience, rather than logic, tells him that while it may be possible to forego lubrication on parts with low frequency/slower interactions – compensating through the use of, say, Teflon-style coatings or the self-lubricating quality of copper – and by reducing friction through the introduction of more favourable angles between other parts, high frequency/fast interaction parts like the escapement will always need oil.

“Until that is, we can make something like a low-frequency escapement, so I suppose you never know,” he laughs. “[But rather than eliminating oil, at least] now there are more intelligent ways of using it, only on those parts that really need it, and stopping altogether on those parts for which lubrication is actually bad over time because it just attracts dirt and dust. But the fact is that [whatever you do] some kind of limit is eventually reached – fatigue happens.”

Even Roger W. Smith – the watchmaker working with the Manchester Metropolitan University on nanotech coatings – has his own kind of scepticism. He argues that if there is an oil-free watch in the future, it is more likely to come not from materials science alone so much as in combination with a serious rethink of traditional watchmaking parts and their interactions. The one-time apprentice to George Daniels – inventor of the “99% friction-free” co-axial escapement, one of the great advancements in mechanical watchmaking of the last two centuries – Smith has since improved on that design with a single wheel version and then a smaller, more efficient one. Smith concedes that some oil is still needed but reckons his watches can now go up to 15 years between services.

“And if we can crack the application of nanotech then I can easily see that being 25 years,” says Smith. “Right now all of the attempts at minimising lubrication seem to me like sticking a plaster on the problem but not actually addressing it. In many respects [commonplace parts] of the watch movement are fundamentally flawed – the lever escapement, for example, is a high friction escapement and even with additional tech would still be inefficient. But I don’t think there’s really any great interest [across the watch industry] in making these kinds of improvements. I think the feeling is that it’s a huge business and we know watches work with current technology – so why bother trying to re-think the foundations?”

WHAT PRICE PROGRESS?

Given the time, effort and capital required to produce something like a lubricant-free watch, its real-world appeal is naturally a matter of price too. As Marcus Wagner, the marketing manager for Sinn notes, there is a point where such developments make a watch uneconomical, which is why so many oil-free watches never leave the development stage. Sinn, like fellow German brand Damasko, has its own lubricant-free technology, a diamond-coated escapement technology unveiled 30 years ago, the first used in a series of watches (currently in six models) and more still in development.

But even for a German brand predicated on more engineering bang-for-buck, Wagner concedes that “it’s a lot of work when possibly the audience doesn’t value the progress (it embodies) enough to pay for it. The problem is that scaling up (these no/low oil technologies) is very expensive. Lubrication remains an on-going experiment for us even as we’re pretty sure that no watch can run with no oil at all.”

Of course, while less lubrication might make regular servicing less imperative, any lubrication means that servicing cannot be eliminated altogether (notwithstanding the idea that anything mechanical, and especially water-resistant, will benefit from some kind of service eventually). “As the situation stands, there is absolutely no lubricating material that can conserve its basic qualities indefinitely; everything changes over time. The length of time that timekeepers will function is thus limited by how much time will pass before the oil will deteriorate,” as the Roret Manuel de L’Horloger watchmaking manual noted in 1825.

Maybe not that much has changed since then. Maybe acceptance of this idea is what keeps much of the industry making incremental advances on what remains, essentially (and, for many, appealingly) 18th century technology. And, as Wagner jokes, “from a purely sales perspective [it could be argued that] expanding the lifespan of a product is kind of stupid.”

HIDDEN COSTS

Those of a conspiratorial mindset might further suggest that this also suits those watchmakers for whom after-sales servicing is a profitable sideline to watch manufacture – and, the more high-tech watch movements and materials get, the more they are beyond the reach of more affordable independent service centres. The same has happened with the computerisation of car engines. This said, with the need to maintain skilled and expensive labour, which takes up time and space, many watch brands might rather dispense with this altogether.

And maybe there is a bigger question here: even if the watch industry could produce a truly lubricant-free watch at a commercial scale, would it offer a clear benefit to consumers? After all, for all that watchmakers might advise customers to regularly service their watches, the cost and inconvenience of this might lead to some scepticism as to how often most of them actually do. It may be creating bigger problems in the longer run, but assuming the watch is wound occasionally and kept in temperatures neither very hot nor very cold – neither a friend to the oil within – it is not unheard of for a modern mechanical watch to run well without servicing for decades.

“Servicing remains a hidden cost of mechanical watch ownership, because it’s neither inexpensive nor quick. We accept the additional inconveniences with, say, cars in part because we’re more knowledgeable about them [through the requirement of legal safety checks, for example] but also because we tend to need our cars in the way we definitely don’t need mechanical watches,” says Sharp, who further wonders whether the escalation in warranties being offered lately is more about distracting customers at the point of purchase from asking awkward questions about the burden of servicing. “I think most people who own a mechanical watch are in the fix-it-when-you-need-to business and not in the mitigating-risk business, like most wait until they’re ill to see their doctor.”

APPEALS TO EMOTION

Here is another idea too: maybe oil should always be part of the mechanical watch because it is fundamental to the character of what a mechanical watch is, and that to keep pushing the application of, among other whizzing advances, the latest materials science is to further dilute that character. It is to further move the mechanical watch away from being an object that, in theory, will still make design and engineering sense centuries from now – as its clock forebears did centuries ago – and towards being a high-tech, specialty-manufactured product that at some point is inevitably outmoded. It is the same objection some feel towards the replacement of the internal combustion engine with electric motors – it is progress, but at what cost to emotion?

There is, agrees Philip Barat, head of R&D at Patek Philippe, a fine line. “The key is to find the right balance: to improve reliability, some technical advances do require less traditional processes, but they always remain within the spirit of mechanical watchmaking,” he suggests. “We use new materials and technologies only where necessary. [Besides which] to improve the longevity and reliability of our movements, it’s not essential to design a watch that is entirely oil-free. The priority is to eliminate lubrication where it is most critical.”

Oil, a little oil or, maybe some day, no oil at all, it pays to recall that the mechanical watch is in part beloved precisely because it is such a mini-marvel of engineering. Felix Baumgartner recalls once being told by his watchmaking teacher that even if the speed of the gears in a watch movement are ponderously slow relative to the turbo-charged engine of a Porsche, because the surfaces of its parts are so small the pressures are much greater. “And so it’s incredible that while the Porsche has to be serviced every year, a mechanical watch only needs it every five years,” he adds. “It’s already performing better than other engines.”