Fired by Fantasy: The Enamel Artistry of Haute Horology

Enamelling is a tedious process, to put it mildly. The raw material must first be ground into a fine powder, and then mixed with a suitable medium (oils or water are both used) to form a paint-like emulsion. This liquid is then applied like paint, before being fired in a kiln to vitrify it – the medium evaporates, while the powder melts and fuses into glass. There are variations to these steps, of course. Some manufactures, for example, choose to sieve the power directly onto a base of either brass or gold, and fire this “layer” of powder directly. Whatever the process, every step is fraught with danger. The product may crack during the firing process. Unseen impurities may surface as imperfections. Colours may react in unexpected ways. There are numerous risks to endure. Why, then, does this technique continue to be used?

Despite all its drawbacks, enamel still has a depth and nuance that cannot be replicated anywhere else. It is also permanent – vitrified enamel is essentially inert and, like noble metals, will remain unchanged a century from now. The different techniques used in enamelling are capable of creating a wide spectrum of products as well, from a single large surface free of blemishes, to microscopic levels of detail in an enamel painting. Perhaps the romantic aspect of this metiers d’art accounts for part of its appeal too; the time and touch of the enamellist is the perfect counterpoint to the watchmaker, with art on one side and science on the other.

Variations on Theme

Enamels are fired at various temperatures – or not at all – depending on their types. Grand feu (literally “great fire”) enamel is fired at around 820 degrees Celsius, although intermediate firings to “set” it may be at around 100 degrees Celsius, to boil the solvent off without fusing the powder. Enamels in general, including those used in miniature painting, may also be fired at around 100 degrees Celsius instead. Finally, there is cold enamel, an epoxy resin that cures and hardens at room temperature.

What difference does it make? For a start, higher temperatures are definitely more difficult to work with, since the enamel may crack during firing, or the subsequent cooling down process. The spectrum of colours used in grand feu enamelling is also more limited, as there are less compounds that can withstand the temperature. The choice of technique boils down to the desired product – for all its drawbacks, grand feu enamel has an inimitable look. A great monochromatic example is the Breguet reference 5177. Enamels, porcelains, and lacquers all share common properties of hardness, durability, and the ability to take on both matte and polished finishes. The three aren’t interchangeable though. Lacquer is an organic finish that is applied in layers, with each successive coat curing at room temperature before the next is added. Porcelain is a ceramic that is produced by firing materials in a kiln to vitrify them. Although enamel is also fired, it only contains glass and colouring compounds, and lacks porcelain’s clay content.

Raised Feilds

In champlevé enamelling, a thick dial base is engraved to create hollow cells, before these cavities are filled with enamel and fired. Because the engraving step produces rough surfaces at the bottom of each cell, the champlevé technique typically uses only opaque enamels. The method allows areas on the dial to be selectively excavated, and for enamels to be mixed freely within each dial. This is done to great effect in the Van Cleef & Arpel Brise d'Été (above and opposite), which demonstrates the brand's decorative chops with not only champlevé enamelling but also valloné and plique-à-jour (discussed later); valloné is a type of champlevé, with more depth and nuance thanks to hill-like reliefs.

Champlevé enamelling’s use isn’t limited to creating decorative art. In Parmigiani Fleurier’s Tecnica Ombre Blanche, for instance, it was simply the most appropriate technique. Although the timepiece has a simple white enamel dial, its surface is interrupted by three sub-dials and an aperture for the tourbillon. This watch was new in 2016 and not only has Parmigiani Fleurier not revisited it, what with the brand's renaissance, but no other brand has explored it either. As noted in our earlier story, the alternative here

would be to make a complete enamel dial, before cutting out the appropriate sections in the middle. One can, however, imagine the risks of doing that.

Is there a limit to the level of details that can be achieved with champlevé enamel? Patek Philippe may have the answer with the Ref. 6002 Sun Moon Tourbillon (right). Apart from the centre portion, which is produced using the cloisonné technique (discussed later), the timepiece’s dial is a work of champlevé enamel – even the railway track chapter ring was milled out in relief, before the recesses are filled with enamel and fired.

Engraving isn’t necessarily the only way to produce the cells used in champlevé enamel though. Hublot put a modern twist on things with the Classic Fusion Enamel Britto, by stamping the white gold dial base to create the raised borders between the cells. This not only reduces the time needed for each dial but also ensures uniformity between them. Subsequent steps, however, remain unchanged: the cells were sequentially filled with different colours of enamel and fired multiple times before the entire dial surface was polished to form a uniformly smooth surface.

Wire Work

Cloisonné enamelling is almost like the opposite of the champlevé technique – instead of removing material from a dial blank, things are added on it instead. The cloisons (literally “partitions”) here refer to the wires, each no thicker than a human hair, that the enamellist bends into shape and attaches onto a base to create enclosed cells. These cells are then filled with enamel of different colours, before the dial is fired to fuse the powder. The wires remain visible in the final product, and look like outlines of a drawing, with a metallic sheen that contrasts with the glassy surfaces of the infilled enamel.

Plique-à-jour (“letting in daylight) enamel can be considered a variation of cloisonné enamel, but the technique is a lot rarer owing to its complexity and fragility. Like its cloisonné sibling, plique-à-jour enamelling involves creating enclosed cells using wires, before filling them with enamel. In this case, however, there is no base. The lack of a backing can be achieved in various ways, but usually involves working on a base layer a la cloisonné enamelling, before filing it away to leave just the wires holding onto vitrified enamel. Since there is no base, plique-à-jour enamelling almost always involves transparent or translucent enamel that allows light through, which essentially creates tiny stained glass windows.

Van Cleef & Arpels has used the above technique to great effect. In the Lady Arpels Nuit Enchantee watch (seen here across both pages), a grisaille enamelled lower section supplies nightime context to an upper section with elements executed in plique-à-jour (the fairy's wings) and façonné enamel (to cradle the yellow sapphires) forms the foreground. Even the surfeit of sapphires, diamonds and rock crystal cannot overwhelm the artistry here.

Hybrid Theory

There are several “hybrid” techniques that combine enamelling with other decorative arts, and flinqué enamelling is arguably the best known given its long history of use. The technique combines guillochage with enamelling – a brass or gold dial is first decorated with guilloché, before layers of enamel are successively applied and fired. When this enamel coating is sufficiently thick, it is polished to create a smooth surface; the final result is a translucent lens through which the guilloché is admired. Depending on the desired effect, the enamel used may be colourless to impart a subtle sheen, or coloured for more visual oomph, like the trio of limited edition Rotonde de Cartier high complications unveiled at Watches & Wonders 2015. Vacheron Constantin has even adapted the technique by using guilloché patterns to mimic woven fabrics in the Métiers d’Art Elégance Sartoriale.

Developed by the husband-and-wife team of Olivier and Dominique Vaucher, shaded enamel (email ombrant) also involves the application of translucent enamel over an engraved dial. Instead of a regular pattern a la guilloché, however, shaded enamel entails the creation of an image in relief. This technique was last used in the Hermès Arceau Tigre, but the watchmaker does utilise other hybrid techniques, seen prominently on the unique Arceau pocket cheval punk.

The final technique here is Cartier’s enamel granulation, which combines enamelling with Etruscan granulation originally used by goldsmiths. The craft requires multiple steps and is extremely tedious, to say the least. Enamel is first worked into threads of different diameters, before these threads are chipped off bit by bit to form beads of various sizes. The beads are then sorted by colour and applied to the dial successively to assemble an image, with intermediate firings to set and fuse the enamel. As different colours of enamel fuse at different temperatures, there is a clearly-defined order for the assembly process; up to 30 firings are necessary, and each dial requires nearly a month to complete. Like shaded enamel, enamel granulation is a very recent development, and Cartier is reviving it in its Maison des Métiers d’Art in La Chaux-de-Fonds.

Metallic Content

Paillonné is among the rarest enamelling techniques today, and practically synonymous with Jaquet Droz, which mainly works on special creations these days. The manufacture did have full-time enamellists who don’t just produce enamel dials, but also train artisans to perpetuate this know-how. The “paillon” here refers to the small ornamental motifs that are created from gold leaf, and are the calling card of the technique. Essentially, paillonné enamelling involves setting paillons within enamel to form patterns, with regular geometric ones being the norm. Emblematic of this technique is the Patek Philippe

Ref. 5077/100G models, as seen here. The technique begins with a layer of coloured enamel that is first fired to set it. Upon this layer, the paillons are positioned, before translucent enamel is applied and fired, thus “locking” the paillons in. Additional steps can be taken to create even more intricate designs. Before the coloured enamel layer is applied, for instance, the substrate surface may first be decorated with guilloché, which basically creates flinqué enamel that is then decorated with paillons over it. Alternatively, the substrate surface can be hand engraved – there are no hard and fast rules to this.

In lieu of regular patterns, Jaeger-LeCoultre opted for a twist on the technique, by distributing flecks of silver randomly on the dial instead. The result can be seen in the Hybris Artistica Duomètre Sphérotourbillon Enamel, whose enamel dial mimics the look of lapis lazuli. While not paillonné enamelling per se, Vacheron Constantin’s use of hand-applied precious powder deserves a mention here. In the manufacture’s Métiers d’Art Villes Lumières timepieces, gold, platinum, diamond, and pearl powders are affixed to the surface of the enamel dial by Japanese enamel artisan Yoko Imai. Instead of being covered with a layer of enamel, these particles sit atop them, and catch the light variously to mimic a bird’s eye view of a city at night.

Brush Strokes

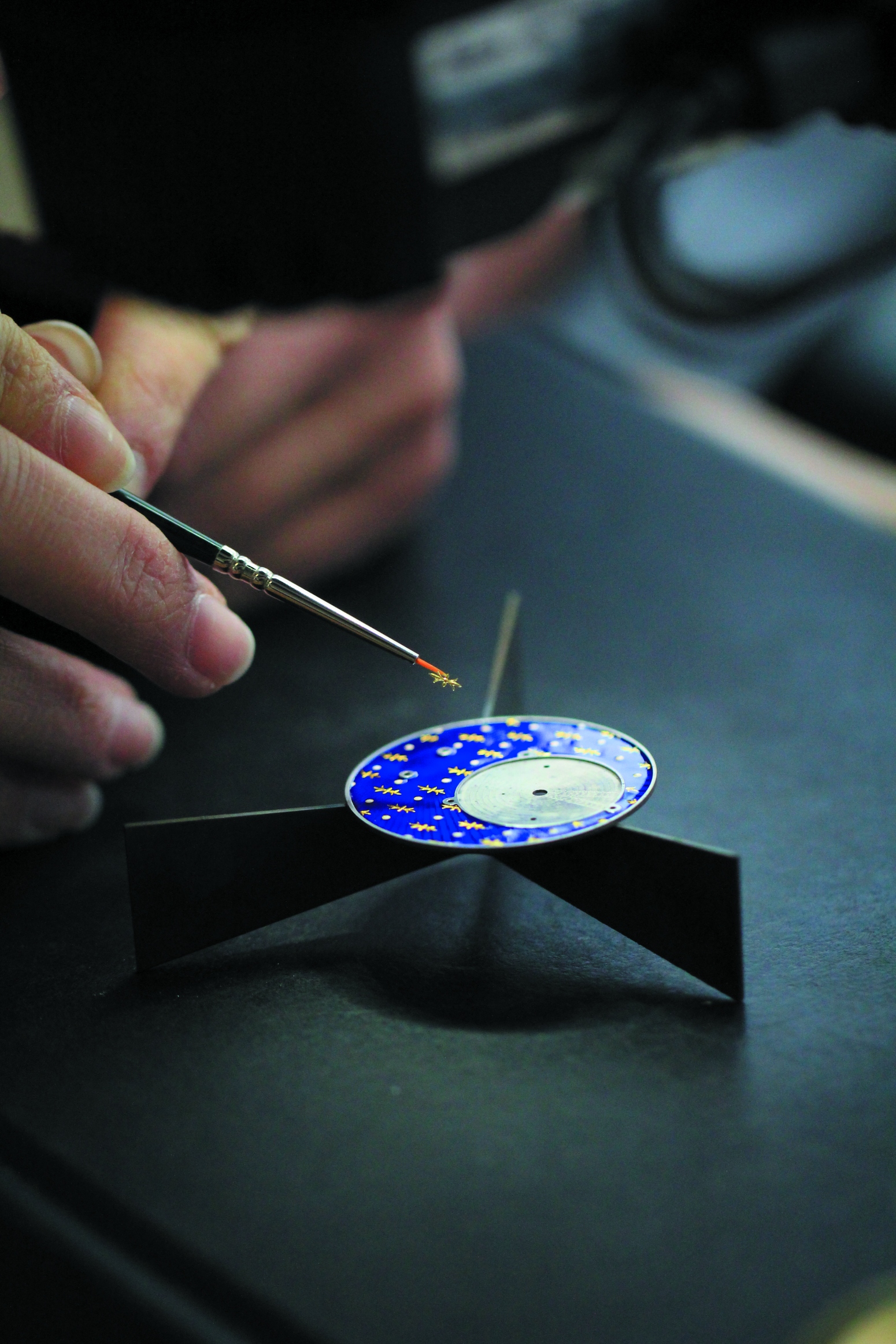

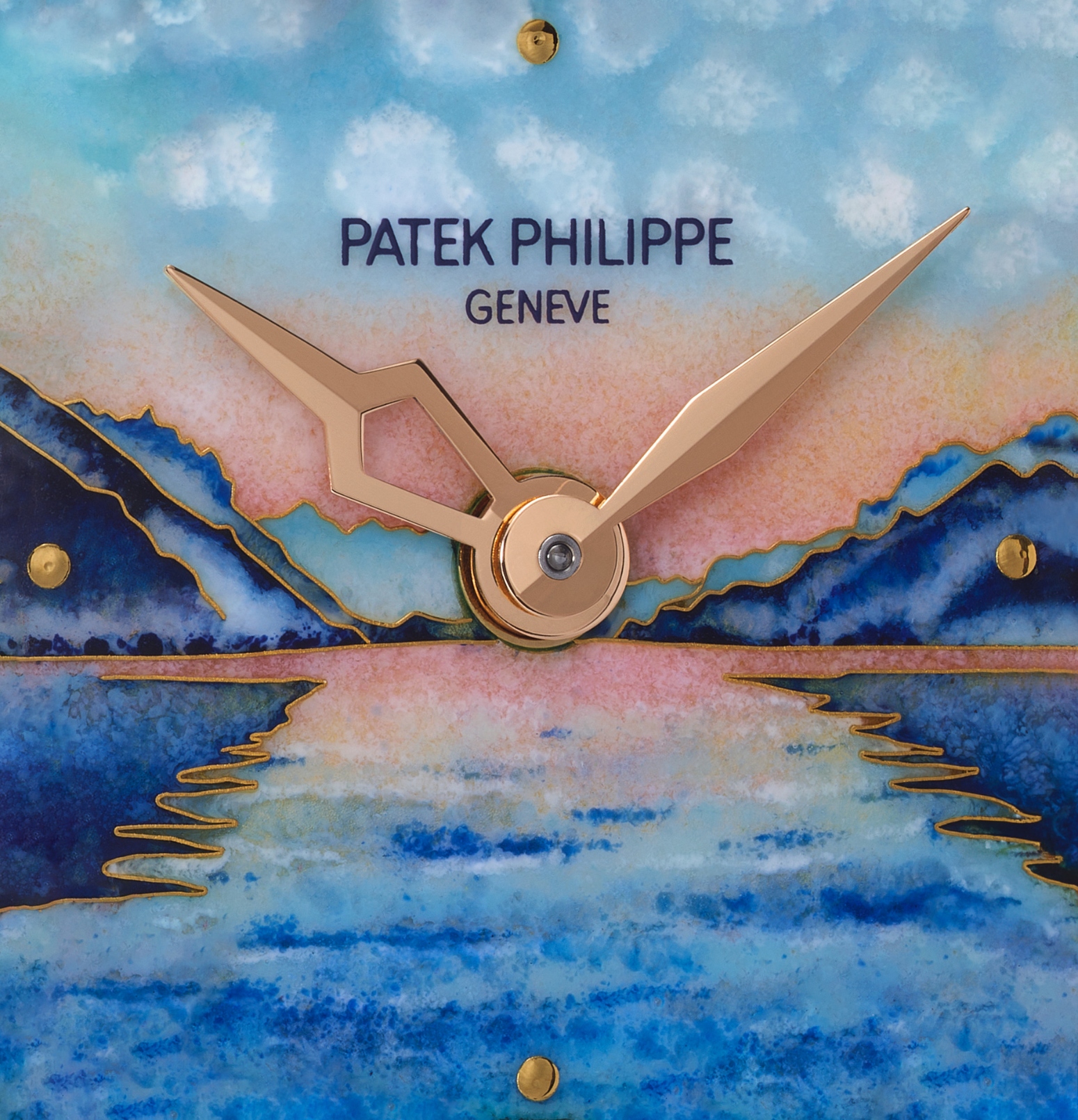

Enamel painting is simply painting with enamel pigments rather than some other medium. The technique is challenging not just due to the canvas’s size, which makes it miniature painting as well, but also because of the multiple firings needed to vitrify and set the enamels, colour by colour by colour. Given the level of detail that can be achieved (as seen in the Patek Philippe Ref. 5531R here), however, this is

one of the few techniques that are capable of making their subjects almost lifelike. Consider Slim d’Hermès Pocket Panthère, which has the eponymous animal rendered in this technique, for example. Jaeger-LeCoultre has many examples, courtesy of its in-house workshops.

Grisaille enamel can be considered a subset of enamel painting, and is a specific method of painting white on black to create monochromic imagery. The black canvas is grand feu enamel that must first be applied, fired, and then polished to create a perfectly smooth surface that’s free of imperfections. This preparatory step is, in and of itself, already very challenging, as minute flaws are extremely easy to spot on such a surface – this explains why most watch brands offer white enamel dials, but black onyx or lacquer dials instead of enamel. Upon this black canvas, the enamellist paints using Blanc de Limoges, which is a white enamel whose powder is more finely ground than normal. To create micro details, fine brushes, needles, and even cactus thorns are used, and the dial is painted and fired multiple times to create the nuanced paintings grisaille enamel is known for.

Owing to its complexity, grisaille enamel is rarely seen. There are brands that still offer metiers ‘dart watches with them though, sometimes even with their own take on the technique. In the Métiers d’Art Hommage à l’Art de la Danse collection, Vacheron Constantin opted to use translucent brown enamel for the dial base, to impart a greater sense of depth, while softening the contrast between the two colours. Patek Philippe and Van Cleef utilise the technique in models featured earlier in this story.

This article first appeared on WOW’s Legacy 2025 Issue

For more on the latest in luxury watch reads from WOW, click here.